How can you develop into an individual who responds to anxiety with creativity rather than retreat? How can you use anxiety as a vitalizing force for authentic living instead of allowing it to paralyze and consume you?

That's the question we were left with after Part 1 of this essay series on Anxiety. This time, you're receiving an unexpected answer.

In Part 1, we talked about how all anxiety starts out as normal anxiety, and that our response to anxiety makes a difference between it being normal or neurotic. We said that the answer lies in moving forward despite anxiety and engaging in it creatively.

However, you don't get to just move forward blindly and force your way through anxiety. Today, I'm explaining why the path to confronting anxiety courageously begins by reclaiming our capacity for sustained attention and deep focus.

As we did last time, we will be referencing the most comprehensive book on anxiety there is, The Meaning of Anxiety, by Rollo May.

To build our argument properly, I need to refresh your memory with a couple of key moments from the previous essay.

"Normal anxiety is, like any anxiety, a reaction to threats to values the individual holds essential to his existence as a personality, but normal anxiety is that reaction which

(1) is not disproportionate to the objective threat,

(2) does not involve repression or other mechanisms of intrapsychic conflict and,

(3) does not require neurotic defense mechanisms for its management, but can be confronted constructively on the level of conscious awareness or can be relieved if the objective situation is altered."

Normal anxiety involves facing threats proportionately and consciously without resorting to repression or defensive mechanisms. Normal anxiety is a movement forward and through the tension of threat and uncertainty rather than a retreat from them.

Regarding threats to our values, we explained that psychological threats, like threats to our identity, authenticity, and freedom, can be as real and as intense as the threat of physical death.

Regarding disproportionate versus proportionate reactions, we explained there is no standardized measure for them. We determine if the response is proportionate not by looking at a scale of reactions or comparing it to others, but by examining its consequences: Do our responses lead to engagement and growth, or to constriction and avoidance? Does our anxiety mobilize creative action, or does it trigger defensive retreat?

But now we arrive at the heart of the question:

How do you become a person who responds to anxiety constructively, courageously, and creatively?

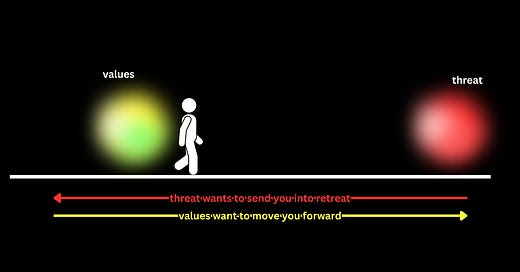

Let's picture anxiety as resulting from a conflict between the threat on one side and the values the person identifies with their existence on the other side.

Rollo May writes:

"A person is subjectively prepared to confront unavoidable anxiety constructively when he is convinced (consciously or unconsciously) that the values to be gained in moving ahead are greater than those to be gained by escape. Then we can see that neurosis and emotional morbidity mean that the struggle is won by the former (the threat), whereas the constructive approach to anxiety means that the struggle is won by the latter (the individual's values)."

Anxiety is the tension between those two poles. Do you protect your current world, or do you keep creating yourself?

On one side, there is the threat. As May implies, there are some values to be gained by escaping. Those are usually comfort, safety, and the illusion of certainty and predictability of life.

On the other side, you have values that are pushing you to move forward so that you may affirm and actualize them. These are the values that are tied to who you are as a unique individual and what your life is meant to express.

It's clear: what makes the difference is not the size of the threat, but the strength of the values pushing you forward.

However, if the term "values" seems a bit vague, that's on purpose. May says that he is using the term "values" because it is neutral and "gives the maximum amount of psychological leeway for the right of each person to have his or her own goals." It is then evident that the values on that help one confront anxiety will vary from person to person.

This is why responding to anxiety isn't just a matter of willpower. It's a matter of clarity. You need to know what you want and what you stand for. And to know that, you need to know yourself. That's where the historical and cultural context of our discussion becomes crucial.

Throughout his works, May repeatedly points out the importance of context. He explains how, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the most common cause of psychological turmoil was "the person's difficulty in accepting the instinctual, sexual side of life and the resulting conflict between sexual impulses and social taboos." Victorian culture was marked by repression - that's why Freud's work was so greatly needed and his impact so profound.

However, as early as the 1950s, May was writing that repression is far from being the primary cause of an individual's inner challenges. Although social taboos still existed in his age, their influence on one's psychological life was nowhere near as strong as when Freud was working with patients. The chief problem of his age, May claimed, was emptiness of the average individual.

So, even though May's insights on anxiety are still relevant for us, we are asked to place the discussion in the context of our age. May, nor anyone else, could've anticipated the extent to which our technological age would make self-knowledge difficult to achieve.

What age and culture do we live in? Constant distraction. Infinite doomscrolling. Algorithmic overstimulation. And, most recently, outsourcing our thinking, creativity, and decision-making to AI. The average American touches their phone 2617 times per day, and the situation isn't any better in the rest of the world.

From the moment you wake up to the moment you go to sleep, you are bombarded with stimuli directed at you by mega corporations that invest billions of dollars into fighting to get as much of your attention as they can.

The result? The average person today doesn't know who they are and can't trust themselves.

Let's make a full circle and bring this back to anxiety. Here is my question to you:

How can you know what values could carry you forward despite anxiety if you never spend a moment alone with your own thoughts and feelings?

The path should be clearer now. Sustained attention to your inner experience allows you to develop genuine self-awareness. Self-awareness leads to clarity about your true values. And clarity about your values gives you the courage to face anxiety courageously rather than retreat from it.

This is why, in our age, confronting anxiety begins with an unexpected first step: reclaiming our attention.

But the task isn't to reclaim our attention just for the sake of becoming more productive. The task is to reclaim our attention as the very foundation of our relationship with ourselves and the rest of the world.

That's why, instead of just blocking out distractions, we must return to practices that help us find our inner center: self-reflection, writing, silence, mindful movement, creative expression, meaningful conversations.

Next week, I'll continue exploring practical steps we can and should take on our journey of confronting anxiety constructively, courageously, and creatively. Until then, here is my challenge for you:

For the next couple of days, at the end of each day, reflect on:

-The amount of time you spent acknowledging what's going on inside you.

-How often do you stop to consult yourself when making decisions? Not "yourself" that family, friends, society, or the church want you to be. But your self.

Thank you for reading.

P.S. If you are an ambitious, creative overthinker, if you have many ideas but struggle to start taking consistent action on them because you lack structure - I got something for you.

One slot for my 1-1 mentorship is still available.

If you want psychological foundation to address your self-sabotage, paired with practical frameworks and accountability to get things done, book a call to see if we are the right fit to work together.

Talk to you soon,

David, the Recovering Overthinker

Thank you for just helping me to understand my situation better. I'm graduating from my degree soon without my father that has passed on my birthday last March. The pressure of this transition in my stage of life has paralysed me for months now. This essay made me remembered how I conquered anxiety in my university years and made me grow into a the person I used to be proud of. I am here to attest that this method definitely works. I used my attention to build the best life I possibly could instead of resenting other people because they are happier than me by engaging in every interaction and ceasing every opportunity to meet and talk to people because that is my value - to find and nurture genuine connections. Joining events and talking to people becomes exciting rather than terrifying me. Now I'm at a different stage of life and I no longer have the same means to express my values as when I was in university. I guess the first step is to find that and I hope that I can reclaim that part of myself that I have lost. Thank you again, and good luck to everyone in their pursuits.

Fantastic essay. I stepped back from my computer while silently nodding, feeling mildly astonished at the weight of what you wrote several times. Thanks for this.